Every day is flooded with fresh harvests in Chitradurga or Kodagu, or with efforts to catalyse the Contests in other districts. A few days ago, Angelina Gregory, Akshara’s Divisional Field Manager (DFM) met the Zilla Panchayat CEO of Davanagere district at a high-level meeting partly motivated by her and the team. The CEO gave weight to it, put his stamp on it, and Davanagere will soon conduct 126 GP Contests, up from 66 last year.

This is not all that Akshara is experiencing by way of stakeholder convergence. The Contests have an inspirational value, drawing in the media as well. This time their role is more supportive, and their contribution inestimable. Akshara teams talk of the fillip media coverage gave Ganitha Kalika Andolana (GKA), Akshara’s Maths Programme, in its nascency.

At a time when the future of the print media is being debated, the marquee names in the Kannada newspaper space, some of the largest circulating dailies, are covering the Contests profusely, with Udayavani, Prajavani, Vijayavani, and Samyukta Karnataka, all aiming the spotlight on them. They’re publishing significant reportage, taking pains to mention by name and designation the participating officials and their full-hearted espousal of the Contests. Maths is often referred to as kabbina kadala; it’s perceived by children as tough and unyielding. Speakers invoke this catchy, pithy Kannada metaphor and turn it around to reassure the children in the audience that kabbina kadalayalla ganitha – ‘maths is not a hard nut to crack’. Newspapers headline their articles with the phrase. Akshara’s name features in the reports as co-sponsor and organiser of the Contests and the team member at the spot is unfailingly mentioned.

Srikanth, DFM, Karnataka and Odisha, who is Akshara’s data storehouse as well, sees a continuous stream of media write-ups this year – 50+ already. That should be a whole season’s output. It’s the GPs that inform the reporters of the Contests and request their participation. “A media story elevates the status of a village,” says Srikanth. Back then, three or four years ago, an article in a newspaper thrilled the villagers, someone always taking the initiative to bring it to their notice, the Akshara team or a community member. With the pictures of their prize-winning children in it, it made for emotional, tear-filled moments. It’s much the same today. To villagers, unseen and unknown, in hamlets seldom if ever heard of, a published story is a powerful statement. They feel acknowledged, like they have a place in this world.

“It is encouragement for the GPs too,” says Srikanth. “They feel inspired to do more and more. More Contests. Neighbouring GPs that held back come forward, saying ‘That GP is in the news. We should also strive to make it.’” There’s that energising, incentivising component to it. The story may be tucked away on an inside page, but the prominent headlines and the colourful picture or two are rivetingly presented. The charisma of the print media is intact, still alive.

Not to be outdone, independent videographers are filming the Contests and posting their content on YouTube. Smaller, local-area players are hardly limiting themselves or staying behind the scenes – television channels, online news portals. Namma Challakere, in its News Flash of November 29, devoted a long column to a GP President who, at a Contest in a village in Challakere block, Chitradurga district, made an evocative appeal for capturing GKA’s potential better. He called for a more committed utilisation of its learning resources to give children a fulfilling maths experience in class.

The credibility aura of the news outlet is undented. Undiminished is the integrity of a published piece, the largeness it confers on the topic featured. With the media as an ally, and the Contests in far-flung schools making the news with unprecedented regularity, the events get a boost, and by ripple effect, the village communities too. “It’s a big thing for them,” says DFM Ranganath. “The media is the medium of information. It touches everyone’s lives. Their stories encourage people and their representatives to trigger the demand side.” A news story goes more places. Awareness is generated. The motivation for another year’s Contests is born.

“There’s a universality about being featured in the media,” says Ranganath. It has a knock-on effect on many of the hurdles facing education. “Above all, it inspires pride in a government school.”

There’s another element that comes into play. The Contests have set a benchmark of merit, and Akshara has a reputation for reliability, perseverance, and most of all, authenticity. Its integrity is unquestioned. As Angelina says, “The GP Contests are a genuine programme. It’s about children’s education. Government school children in villages. Everyone is interested. Everyone is concerned.”

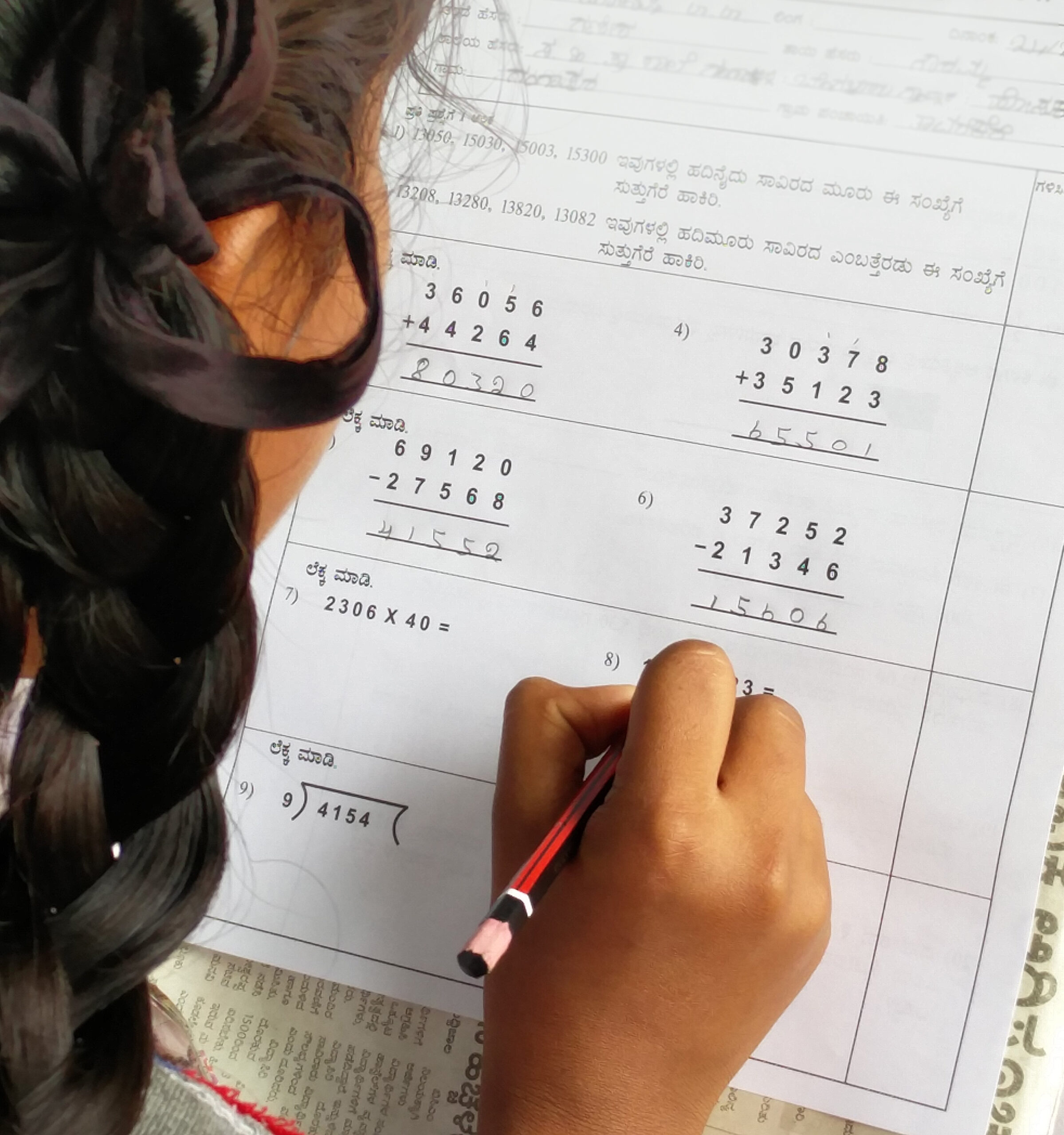

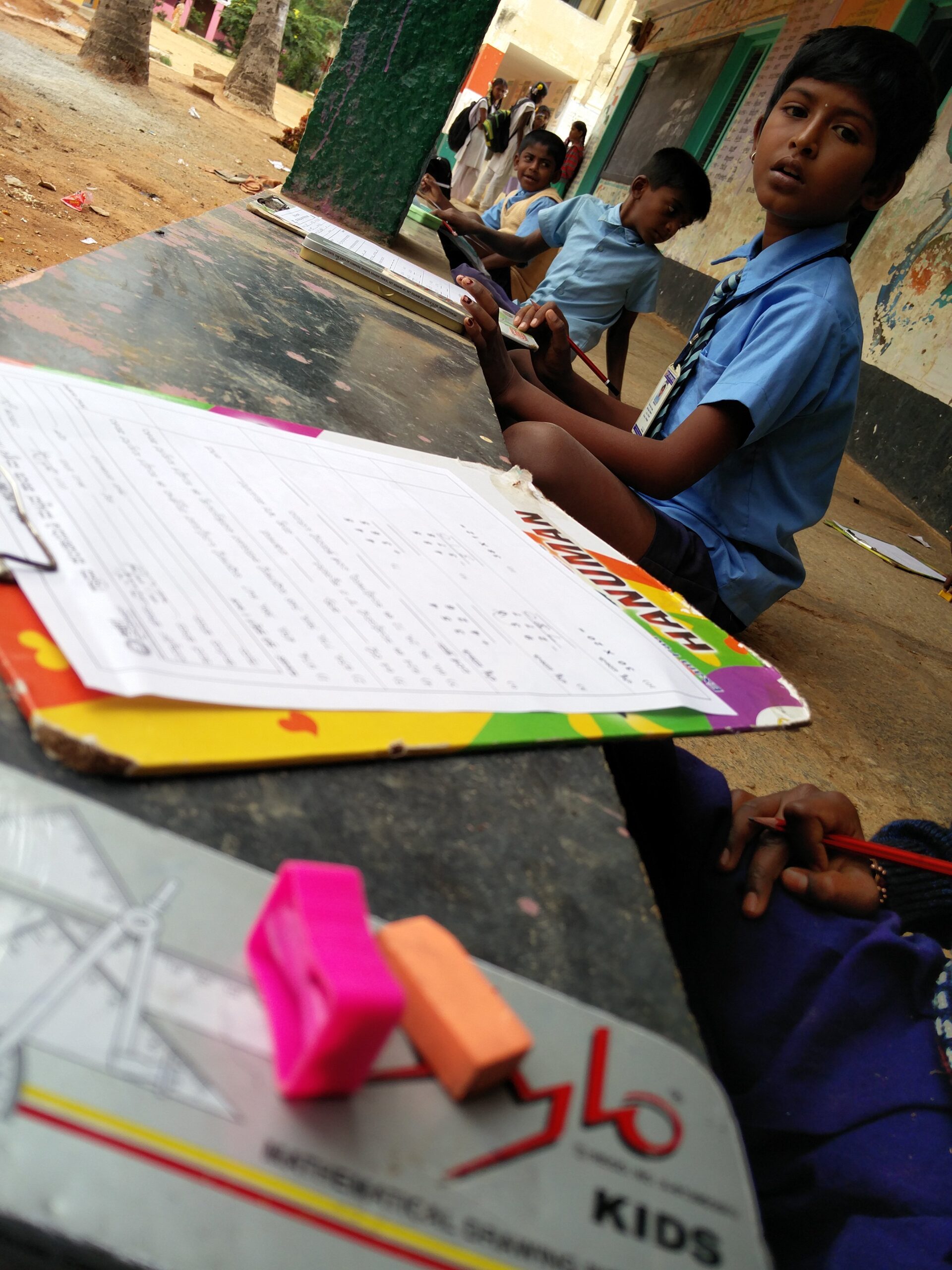

The magnetic quality of the Contests hasn’t blunted with the years. Starting 2016-17 when Akshara on its own held 216 Contests in all of Karnataka. If anything, it’s stronger now, has more drawing power. The function the GPs organise at every Contest is solemn and celebratory at once, the lighting of the lamp setting an intention. The awards ceremony is solely about the children, phone cameras clicking, and the pride and validation of prize-winning.

Every Contest is also a human story of achievement, the bittersweetness of missing a winning spot by a single mark, of saddening failure. A news story is seldom without a picture emblazoning it. It’s usually of the prize-winners displaying their commendation certificates or receiving their cash awards. Ranganath knows children who cut these reports and treasure them in the pages of their notebooks. They never tire of showing it around to family, friends, and the community. “See, my picture. This is me.” To them, the newspaper is a forum reserved for dignitaries, personages, and celebrities. “They feel like a star,” says Ranganath, some of the starriness rubbing off, the glory all theirs, to be gracing these pages. “It’s a forever experience,” he says.

News reports are coming in from Raichur and Yadgir districts, and Hassan has just done what Mandya did the other day. The district’s 267 GPs conducted 267 Contests in a single day on December 4. Another summit, another enormous effort bearing fruit. This is no first flush. The enthusiasm, the urgency, is unabated. The expectation is 4000+ Contests in Karnataka, with 5,00,000 children participating. Success is the flavour of the season. But even as it savours this victory lap, Team Akshara is pragmatic and measured, focused on the truly big goals. The effective use of GKA in maths classrooms, GP Maths Contests in the whole of Karnataka, and better learning outcomes. Till then Akshara can scarcely afford to take a breather.